To End the Pandemic, U.S. Must Look At The Air We Breathe

TROY, NY (07/29/2021) – An air quality engineer warns the COVID-19 pandemic won’t end until Americans clean up our indoor air.

“With variants on the rise, all the talk this summer has been about vaccines. Now we’re hearing about masks again, which feels like a step back for most of us,” said Jeremy McDonald, 54, a professional heating ventilation and cooling (HVAC) engineer with New York-based firm Guth DeConzo Consulting. “But when it comes to preventing the spread of airborne viruses like COVID-19, we also have to improve the quality of the air in our indoor spaces. As the seasons change, it seems like we’re going back to old tired strategies that haven’t gotten us out of this mess. It’s time to listen to the engineers: it’s all about the air.”

In a July 26 essay titled “Moving Beyond COVID-19: It’s Time to Look at the Air We Breathe,” McDonald argues that President Joe Biden’s “American Jobs Plan” must include improvements to our indoor air quality (IAQ) infrastructure if we are to finally beat the COVID-19 pandemic and improve our defenses against future pandemics and common day-to-day air quality maladies. Toward the end of July, COVID-19 cases began to surge in parts of the United States and The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revised its mask guidance to once again recommend Americans wear masks indoors, even if vaccinated.

McDonald encourages improvements to ventilation and the use of high-performance air filters and other air purification technologies where appropriate. Buildings that have deferred maintenance and investment in modern HVAC may require more complicated and expensive solutions.

“Although some buildings may require an expensive investment, we need to weigh this against the cost of our health and well-being,” McDonald writes. “Certainly, when considering our health, fixing ‘sick’ buildings is a much better choice than fixing ‘sick’ people.”

Yet, McDonald says there are plenty of low cost or no cost solutions that can drastically improve IAQ, such as cracking a window which reduces the intensity and quantity of virus particles and their ability to spread to more people, using air purification technologies, and simply ensuring that buildings meet the spirit of building code requirements for minimal fresh air for buildings.

There is a historical precedent for this common sense strategy, which McDonald notes in his essay: “In response to the Pandemic of 1918 when more than 20,000 New Yorkers died, ventilation was seen as one of the key attributes to protect residents from the devastation of the pandemic. Back then, New York City officials dictated that building heating systems were to be designed and sized to operate with all the windows open, since it was recognized that ventilation was key to purge the virus from indoor spaces. If it worked 100 years ago, it will work today.”

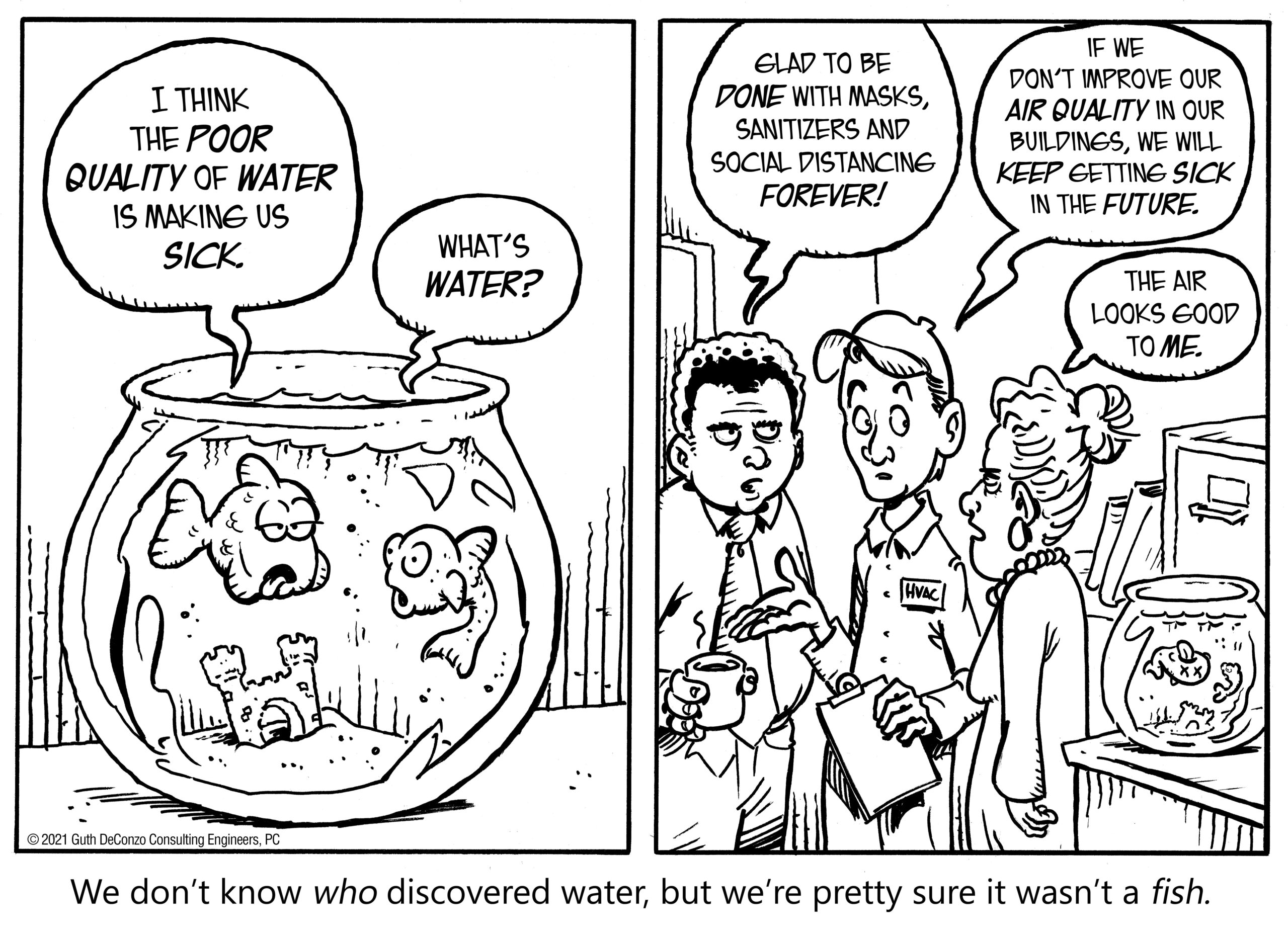

One of the main challenges in getting people to pay more attention to poor indoor air quality is that the problem is invisible, an issue McDonald comments on in an original cartoon he commissioned to get his point across.

In the first panel of the cartoon, two fish swim in a bowl. One fish says “I think the poor quality of the water is making us sick.” The other fish asks, “What’s water?” In the second panel, two office workers and an HVAC engineer stand near the same fish bowl. “Glad to be done with masks, sanitizers and social distancing forever!” says one office worker. “If we don’t improve our air quality in our buildings, we will keep getting sick in the future,” the engineer chimes in. “The air looks good to me,” says the other office worker. Beside her, one of the fish in the bowl is floating upside down with X’s for eyes, indicating it has died.

The caption below the cartoon reads: “We don’t know who discovered water, but we’re pretty sure it wasn’t a fish,” which is a modern proverb attributed to various sources. That saying, McDonald feels, sums up our own troubled relationship to air quality — because air is so fundamental to our existence, most of us don’t even think about it, he notes, but HVAC engineers think about air every day, all day and it’s time to listen to them in the fight against airborne illness.

“My frustration, which motivates me to write and speak out on the issue of air quality, is that our leaders are not getting it and they aren’t listening to engineers,” McDonald said. “But the public health officials aren’t really talking about indoor air quality either, so a lot of politicians probably don’t want to go against the narrative.”

McDonald goes so far as to suggest that some of the anti-vaccine sentiments may stem from incomplete messaging that does not address indoor air quality.

“Some of the resistance to masks and vaccines might be because people know, in the back of their mind, there’s something missing from the common messaging that is ringing hollow 18 months into this pandemic,” McDonald said. “We are constantly hearing ‘Wash your hands, wear a mask, and socially distance-where possible.’ We need to add simple, yet time-tested ventilation strategies to our messaging, which we all know implicitly makes sense to folks from all political persuasions.” Perhaps with improved messaging from our leaders and initiatives to fix our broken HVAC systems we can truly address this pandemic without arguing about the viability of masking and vaccines, he added.

McDonald is clear that vaccines are a key tool in beating this pandemic. But, without addressing the fundamental issue of indoor air quality, we may be putting a “BAND-AID” on the current problem, missing out on the opportunity to improve public health for the long term, he notes.

Fortunately, McDonald says that many of his clients understand the need to address the air quality in their buildings and are taking the necessary steps.